The early years

In 1938, American pathologist Dr Dorothy Andersen coined the term “cystic fibrosis of the pancreas” based on her autopsies of children.

In those days, children simply didn’t live long enough to develop severe lung disease from the condition, but died from malnutrition due to failure of the pancreas which developed cysts and became scarred. How CF got its name wasn’t to do with the lungs at all!

Further problems with salt and water loss through the skin in children during the 1948 New York heatwave, lead to Dr Paul di Sant’Agnese, seeing infants sick with dehydration, which led to his discovery that the sweat of children with CF had abnormally high concentrations of salt, leading to the ‘sweat test’ – which is still used today. This resulted in better diagnosis and started specialist services for children with CF in the US and Europe, which improved care and increased survival.

In 1965, Royal Brompton established the first adult CF service in Europe, and possibly anywhere in the world, and for this we are indebted to Professor Margaret Mearns, who was a paediatrician at Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Hackney.

Many children were living beyond early childhood and Professor Mearns was fed up with these young adolescents having nowhere appropriate to be treated, so she came to Royal Brompton and trained Sir John Batten – who had been a consultant physician at the hospital since 1959.

Professor Mearns and Sir John started by running clinics together with older children and young adults. As an aside, in 1974 Batten was appointed as Physician to the Queen – but still continued his work at Royal Brompton.

The specialist treatment of adults with CF really wasn’t ‘a thing’ when Professor Mearns started, it didn’t exist as a specialty, and she was willing to take it on as a special interest. We owe her a great deal.

CF treatments in the 1960s and 70s

One of the predominant treatments at the time was mist tents. They were a way of delivering air, which was humidified, to patients’ airways. It would help to liquefy secretions and, in so doing, make them easier for the patient to clear the mucus.

One of the predominant treatments at the time was mist tents. They were a way of delivering air, which was humidified, to patients’ airways. It would help to liquefy secretions and, in so doing, make them easier for the patient to clear the mucus.

They probably did have some clinical benefit, but now would be recognised as a cross-infection nightmare: we know now, of course, that bugs would simply recirculate through the water droplets. But they were used right up until the early 1980s.

The first independent, systematic physiotherapy-based treatment for airways clearance was developed at Royal Brompton by Barbara Webber in the 1970s. This was called ‘postural drainage’, where you literally tipped people upside down. We don’t do that anymore, although it did work.

Professor Margaret Hodson ran the service at Royal Brompton with Professor Duncan Geddes for nearly 30 years. Professor Hodson was one of the first people to systematically use inhaled antibiotics for children and adults with CF.

Both are still involved in the hospital’s work: Professor Hodson is a chaplain, and Professor Geddes sits on Royal Brompton & Harefield Hospitals Charity’s Board.

The breakthrough of the '80s

The decade saw two huge discoveries, one right at the beginning and one right at the end. And we found that most of the hypotheses up until then had been wrong.

In 1980, a team at the University of North Carolina discovered that the disease was related to chloride and sodium ions within CF cells – they understood the mechanism of how it caused the condition nearly ten years before the gene was discovered.

The CFTR gene itself was discovered in 1989 by a team of researchers led by Dr. Lap-Chee Tsui in Canada. It was, in fact, the first disease-causing gene to be identified in any disease, so this was one of the most significant breakthroughs in human genetics.

Once they started to look for the gene in the mid-1980s, it took them three to four years to find it. With modern gene sequencing, we could now do that in an afternoon!

Some people were wildly optimistic following the discovery of the gene, and the implication that gene therapy would follow, but that turned out to be a whole lot harder than anybody imagined.

The reason why we thought it would happen in five years was that the mutation that causes the disease was now identified and so a specific for the disease treatment should follow.

Over the next 30 years, however, CF geneticists have found 2,000 different variations of that mutation.

So, we thought we’d found the Holy Grail, but in fact we’d just opened the door to an enormous challenge of delivering transformative therapies for CF.

1990s and 2000s: searching for transformative therapies

To cut a long story short, the United States CF Foundation, in partnership with Vertex Pharmaceuticals, explored small molecule drugs directed at fixing the CF protein in cells while Professor Eric Alton and his team at Royal Brompton developed a gene therapy programme for CF – the only clinical programme in the world for quite a time.

Small molecule therapy has led to a range of modern CF drugs: including ivacaftor, lumacaftor, tezacaftor and new triple combinations, which I will come on to shortly. Gene therapy has been encouraging but has turned out to be harder to deliver to the sick CF cell than small molecules.

But there is now a renewed interest in gene therapy, particularly with the advent of gene editing – really cool technology that means you can edit genes rather than replace them, so you could theoretically edit the mutation and fix it by cutting the bad bit out, and then the DNA replication system copies it without the mutation.

This is particularly of interest for people who have what are called ‘stop mutations’ which, put simply, stop reading along the instructions of the DNA, so the cells can’t carry on making what they’re intended to.

Of the 2,000 CFTR gene mutations, about ten per cent are stop mutations. These can’t be treated with drugs because drugs work on the protein: with a stop mutation, you don’t make the protein in the first place. That’s now the focus for gene therapy.

The future for CF drugs

I think the success of the drugs that have been developed is, firstly, they have a real impact and, secondly, for patients, taking a tablet is such a simple way to administer them.

Triple therapy trials have now started internationally, and in London we’re working together with King’s College Hospital, Great Ormond Street Hospital, Barts Health, Frimley Health and Lewisham and Greenwich NHS trusts. We’re focused on making sure we get the trials done quickly, and ensuring fair access to everyone with CF in London, through a Cystic Fibrosis trust grant.

If the triple therapy combination works, and early trials are very encouraging, it’ll work for 90 per cent of people with CF and could possibly extend their survival in the region of 15 to 20 years. We’re very excited because there’s been nothing like this in our lifetimes as clinicians.

There are, of course, the remaining ten per cent worldwide – those with stop mutations – for whom drugs simply won’t be effective. Of course, we all hope that further work with gene therapy will unlock treatments for those people, and gene therapy trials at Royal Brompton are continuing.

We’ve improved airway clearance, antibiotic therapy, and the advice and guidance around nutrition. These have made important differences by improving symptoms and increasing lifespan. It’s been a story of improving how we deliver services, how we deliver care, how we recognise specific infections and improving how we treat them.

It’s been hard work for parents and people with CF, but it’s kept people living longer and longer. It’s been a story of developing really exceptional care, rather than ground-breaking medicine.

This new small molecule therapy is the first ground-breaking medicine which treats the basic defect and transform the lives of people with CF – it is the first time in my 30 years of working in CF there’s been anything like this.

Putting CF patients in the driving seat

If triple therapy medicine gets approved and funded, we’re going to be caring for a group of people with CF who are feeling much better, are far more able to work and enjoy life. So, the way care is currently organised isn’t going to be relevant to them anymore. People don’t want to come to hospital every couple of months – they have lives to live.

That’s the thinking behind developing our brand new digital CF service, where people can have an appointment online, take lung function tests on their smartphone, use a home-testing service for blood tests and have prescriptions delivered to their door.

This is relevant now, but will be even more relevant in future when people are much healthier. We’re working really closely with people with CF on this, as they are the people the service has to work for – and they have much better ideas than us.

It reminds me of when I was thinking of buying my son a new laptop for his birthday. He said, “No-one uses laptops anymore dad, we’ve got phones, laptops are just something you old men carry around!” In a way, that says it all.

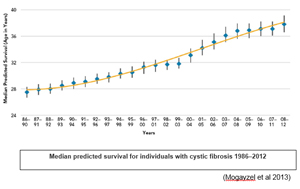

CF is a really tough disease to have, but the combined efforts of people with CF, parents, CF clinical and research teams, support from the CF Trust and a real focus from the pharmaceutical industry have improve survival from about one year in the 1950s to nearly 50 years in this decade. New therapies in development will continue to enhance the lives of people with CF and extend survival even further.

This is a fitting testament to the ceaseless hard work of patients, their families and friends, and the numerous NHS staff – of too many professions to list – and research teams who continue to care for people with CF and progress new treatments to transform lives.

Professor Stuart Elborn is a consultant in respiratory medicine and centre director for specialist adult cystic fibrosis.