To celebrate British Science Week at Royal Brompton and Harefield hospitals we’re highlighting some of the important work our researchers are tackling.

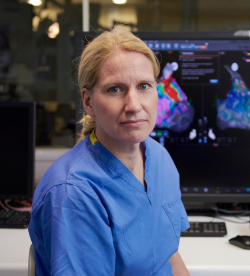

In this instalment we asked Professor Sabine Ernst to reflect on the research she does and how it translates into her clinical work.

Professor Ernst is a consultant cardiologist and invasive electrophysiologist. In 2019, she became a professor of practice in cardiology through the National Heart and Lung Institute at Imperial College London, being formerly a reader in cardiology.

The beauty of research and why it motivates me

The beauty of research and why it motivates me

My research revolves around finding new ways to understand and treat cardiac arrhythmias. This is an integrative approach that involves advanced 3D imaging of an individual’s heart combined with understanding the electrical abnormal activity that is causing the heart to beat too fast or irregular. Nowadays, mapping of the electrical activity can be done invasively by navigating catheters inside the heart, but also non-invasively whilst the patient is still on the ward.

My favourite thing about research is its creative element, where one can tackle a specific aspect of health and try to improve patient outcomes. As a clinical researcher, my work has a direct effect on patient lives so if I am able to cure a patient’s cardiac arrhythmia, I know that I’ve helped take away one of the worst impairments of their life. That is of course very gratifying and motivates me to keep helping to innovate new therapies.

My research

I am currently working on a number of different research projects, one of which involves trying to combine non-invasive 3D mapping, which is performed on the ward with remote-controlled magnetic navigation. 3D mapping uses the data from several imaging techniques (i.e. ECG, CT scan) to produce cardiac maps that allow us to characterise abnormal rhythms of the heart.

My team and I are also working on research that aims to make electrophysiology (EP) studies less invasive. EP studies help us to diagnose abnormal heart rhythms and are normally carried out using catheters that are inserted into a vein in the groin. Our research will be looking to see if the procedure can be done through the arm rather than the groin, which we believe will be less invasive and reduce the amount of bed rest a patient would need after the procedure.

Another research project I’m working on is looking at the possibility of eliminating radiation exposure during EP studies for both patients and staff. At the moment, EP studies are conducted using a type of x-ray scan (fluoroscopy) and our research will look at the effectiveness of a method known as 'ZERO fluoroscopy' and whether it is as effective.

My motivation

The main reason I do research is because I always want to try and improve the outcomes of catheter ablation procedures and make the procedure more considerate for both patients and staff. For example, radiation exposure is a risk not just to patients but for the staff involved in the procedure, who have an increased risk of malignancy due to their professional exposure to x-rays.

In clinical research all achievements, per definition, should directly result in improvements in patient care and outcomes. That is the beauty of it. However, this also poses a risk as you just can’t simply rerun the experiment with slightly changed conditions if the result was not what you expected.

Non-clinical research has more room for error, whilst clinical research has to get it right pretty much the first time. The reward is naturally very high and of course we test novel approaches in phantoms and animals first, but some conditions can’t be simulated, and one has to bite the bullet to do ‘first in human’ research in some situations.

The future

I personally believe that telerobotic interventions are the next big thing in cardiology. Whilst we are already performing robotic procedures (as the only centre in the UK with a robotic system in the electrophysiology catheter lab), mostly in complex patients with congenital heart disease, I believe we will be able to carry these out in other centres via telerobotic platforms. In this way, the expert operator will be able to treat more patients and support local teams. This is of greater importance in recent times, where the pandemic has meant that patients and physicians aren’t able to travel as easily for treatments.

Read the other posts in our British Science Week 2021 series: